I've been blogging about bad girls for about two years now, so I thought I'd go back to the beginning and remember why the wildest women in history (and modern times) became my lifeline.

It starts like this:

One fine summer day in 1852, a chronic alcoholic and morphine abuser named Canning Woodhull visited the Mount Gilead, Ohio, home of Victoria Claflin. A fourteen-year-old girl with a calm and thoughtful demeanor, Vickie had taken to her bed so she could speak at leisure to the unseen powers of the air who regularly visited her.

Though weak, Victoria radiated loveliness, and the 28-year-old doctor prescribed a cure of fresh air and marriage. Vickie accepted, happy to leave the house where her father regularly beat and starved her when she resisted appearing as a clairvoyant in his traveling medicine show. “My marriage was an escape,” she later said. It was also a foolish indiscretion that permanently changed the direction of Victoria Woodhull’s life. Only a few days after the couple wed, Dr. Woodhull went on an all-night bender at a whorehouse, the first of many.

A few years and a couple of children later, Victoria finally came to her senses, asked herself “why should I any longer live with this man?” and answered the question with a trip to divorce court. The same powers of the air who had visited Vickie in her youth remained by her side throughout her life, telling her she was destined to become the ruler of the world. And indeed, after leaving her husband, Victoria Woodhull became the first woman to open a Wall Street stock brokerage, the first woman to publish an American newspaper and, in 1871, the first woman to run for US President. She was also an outrageous proponent of free love who shocked America with her libertine views.

Wow, I thought the first time I read about Vickie, this woman’s marriage sounds a lot like mine. I, too, had gone off and gotten married in an attempt to start a new chapter in my life, but my husband, I'll call him Jack, had turned out to be a rageaholic drunk and our marriage was not only no fun, it was a disaster. A disaster that took me a couple of years to get into, a year to recognize for what it was, and yet another year to escape.

Although my marriage to Jack was the biggest mistake of my life, exiting it was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I’d always been too nice for my own good and too afraid of hurting people.

I’d met Jack on a business trip to small-town Pennsylvania, and moved to a place I now call “Tearful Valley,” but my marriage, my hoped-for bucolic ideal, slowly turned into a series of broken promises, silent anger and empty bottles of beer and vodka. I thought I was staying in the marriage to make an effort to fix it, but the truth was that feelings of guilt, pity and failure prevented me from leaving.

Looking back now, this is the part I hate to think about: Jack’s constant verbal abuse chipped away at my self-esteem and kept me down in the emotional muck right alongside him. I had no strength to resist because I was unfamiliar with the person I’d become, and it took the strength of my friends, family, marriage counselor and Al Anon (my equivalent of the powers of the air) to give me the courage to save money, secretly store my belongings and meet with a divorce lawyer. In short, I was preparing for the awful moment when, like Vickie, I could ask “why should I any longer live with this man?” and answer the question by leaving him.

It was no accident that I read up on Victoria Woodhull shortly after leaving Jack. I was, in fact, on a quest to find women like her, a quest that began when I received a phone call from my rich and somewhat eccentric cousin Kent in London. I had only recently loaded my belongings in my car, driven away from Pennsylvania, and gone home to family in Chicago. But I was unsure about my next move.

Cocooning with the people I loved best, pleasantly numb and returned to a childlike state, I was doing little more than spending hours on the phone with friends, watching television, sitting in coffee shops reading, and looking for a job with such apathy that I might not have known what to do if one was offered. In other words, I’d stopped crying and was, in a strange way, beginning to enjoy myself, but to a rational observer I was still a confused mess.

Naturally, I assumed that Kent was making a sympathy call when he began our conversation by telling me about a notorious woman from the Byzantine era. I didn’t know why Kent mentioned her, but I played along—our conversations have always covered a lot of territory.

“Joycie, have you ever heard about Empress Theodora of Constantinople?” Kent asked me. “I learned about her at a dinner party. She started out as a prostitute in the circus and ended up marrying an emperor. She would go onstage and they would sprinkle birdseed on her privates, and a flock of geese would peck at them until she climaxed.”

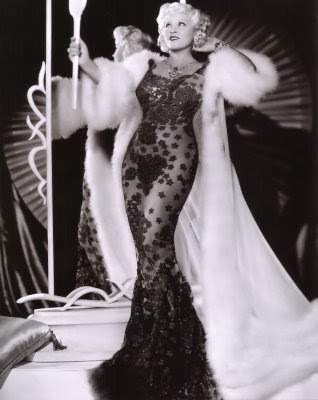

I laughed. “No, I didn’t know about Theodora. But Mae West—now there was a sex goddess for the ages. She’s kind of weird but very luscious in her movies.”

“And what about Catherine the Great,” Kent said. “She was outrageous.”

“Do you really believe that story about how she died underneath a horse when she was having sex with it?” I said. “I wonder if that’s really true.”

“Joycie,” Kent said, and from his tone of voice I sensed that our conversation was shifting into new territory. I realized that it wasn’t just because he felt sorry for me that Kent was calling, and he was leading me there. “Joycie, how are you anyway? What’s going on with you right now?”

“Oh, you know, the usual. No man, no baby, no job, no home, no life. I’m screwed.”

“Are you really getting a divorce? Where are you going to live? Do you have any plans?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I’m trying to figure it out. I’m probably going to stay in Chicago so I can be near family.”

The other end of the line went quiet, and I could tell that Kent was not best pleased with this idea. He thought staying in Chicago would be a bore.

“Joycie, why don’t you come to London instead? Why don’t you come here and study bad girls for awhile? Bad girls like Theodora. I’m working on a project about them, and I need someone to do the research,” he said. “I want it to be you. Seriously, I want you to think about it.”

This is where the logic broke down and my life got interesting. Kent wanted to know about bad girls, for some complicated reason that involved him getting his heart broken and wanting to sublimate it into an art project, but he didn’t have time to spend digging through dusty old tomes in the British Library. That would be my job. He knew I was a writer and would have the patience to read tons of books. Plus, he thought it would be good for me to get away from America and think about life for awhile. And bad girls. Think about life and bad girls and go out drinking together.

Kent had a flat in Notting Hill, where I could live as I studied Empress Theodora, Catherine the Great, Mae West and anyone else who interested me. He would pay my expenses, and I could hang out with him when he wasn’t busy and tell him about all the bad girls I was discovering. In the summer, he added, I could go to France and stay at his villa in the Cévennes Mountains, where he wanted to create something like an art colony or a commune with posh overtones.

I would have been a fool to refuse, so of course I said yes to Kent’s crazy proposal, and this is how our Bad Girls Project began. Why not? It sounded like fun. People have gone off on all sorts of weird expeditions for even less reason. And I had nothing to lose at that point in my life. But I was less certain about how much time I wanted to spend on the project, imagining that at some point my real life, whatever that was, would have to begin again.

Before I left the States, I decided to do a little research so I could better understand what I was getting myself into, and this led me to my first bad girl, a dark angel who cajoled me to follow my destiny as surely as the powers of the air had cajoled Vickie to follow hers. She was soon followed by others.